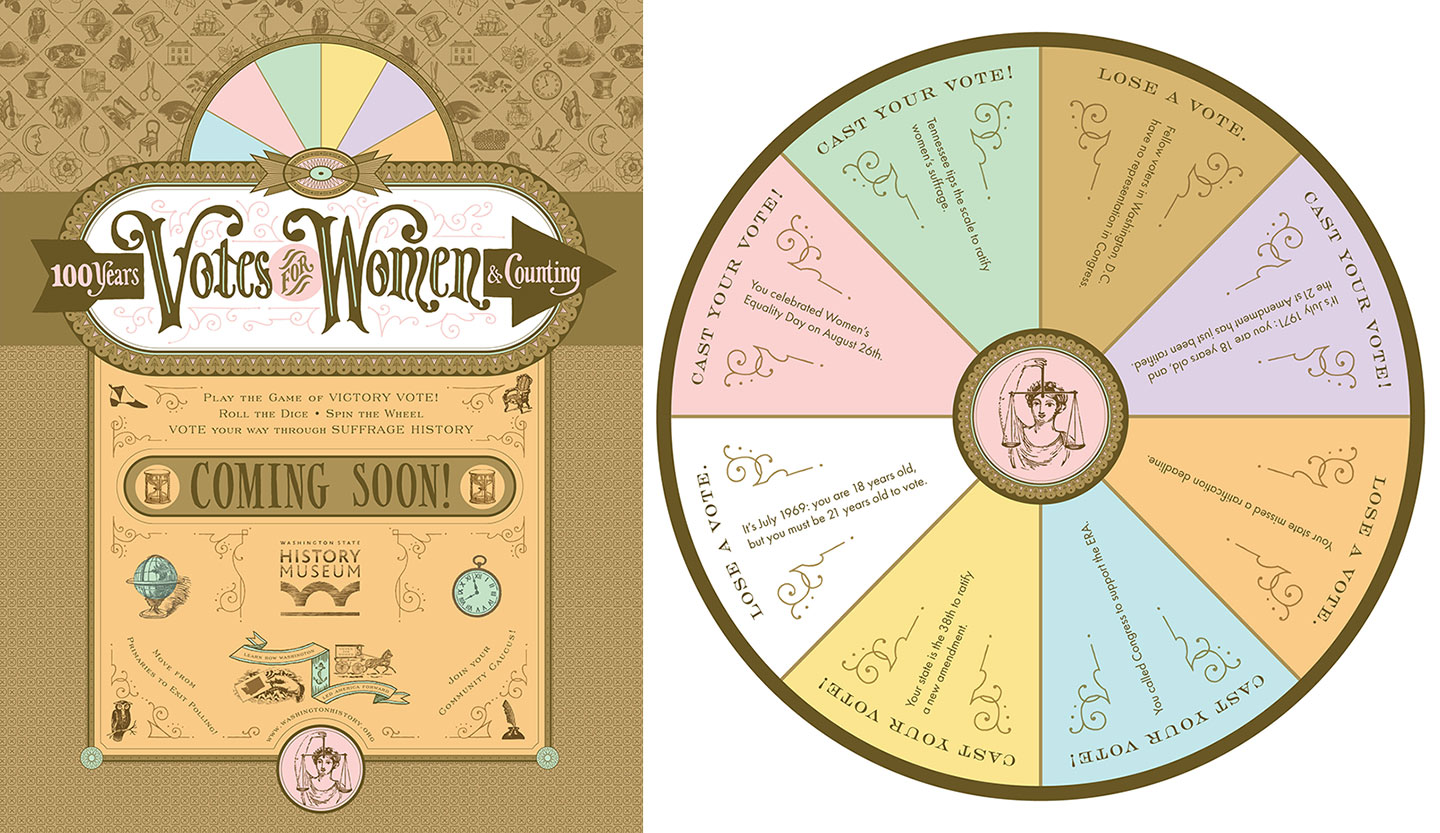

Today, August 26, 2020, is Women’s Equality Day — and also the 100th anniversary of the certification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, when it became the law. We chose this anniversary to release our 30th Dead Feminists broadside: our series began with suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, after all. Yet we knew back in 2008 that Stanton was a problematic choice. She, and most white suffragists, deliberately excluded their Black peers, and resorted to racist rhetoric in their campaigns to further distance themselves from civil rights efforts of the day. When the vote was won — supposedly for “all” women — racist legislation and loopholes effectively disenfranchised many women of color for decades to come. Even today, with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on the books, women everywhere, particularly Black women, face breathtaking voter suppression and barriers to enfranchisement.

We keep returning to this historical and contemporary inequality through our work on the Votes for Women exhibition at the Washington State History Museum (WSHM). Again and again we are reminded that the victory of the women’s suffrage movement was incomplete, and will remain so until the day that voter suppression and disenfranchisement are ended. We also wanted to tell a more complete story of the Black women behind the suffrage movement — so our research (and output) for both the museum and our broadside overlap in many places.

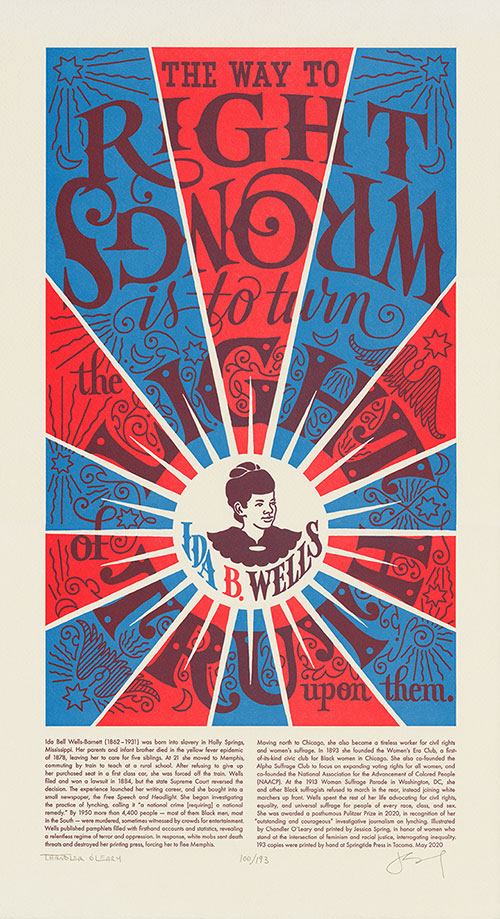

The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.

– Ida. B. Wells

For our 30th broadside, we feature the words and work of a Black suffragist, to tell the story of the marginalized women who fought for the rights of every woman, regardless of race or class. As we spent nearly a year developing the design, the meaning behind our print changed and evolved.

Our broadside was initially intended to mark the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States, and simply tell the story of Black suffragists and how their work resonates today. As 2020 unfolds, however, our print has also come to represent the twin crises of the pandemic and worldwide protests in response to police brutality and extrajudicial murders perpetrated against Black people. These crises have highlighted and exacerbated the systemic racial inequality already present in American society — as well as the responsibility of white women to use our rights and privileges against this injustice.

Civil rights activist, investigative journalist, suffragist, and community organizer Ida B. Wells is heralded as one of the mothers of intersectional feminism — referring to a term coined in 1989 by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how race, gender, and class often overlap to complicate issues of inequality. Wells devoted her entire life’s work to this intersection, fighting for women’s rights and racial justice along multiple fronts.

As a suffragist, Wells was active in the women’s club movement, particularly after she relocated to Chicago from the South. In 1893 she founded the Women’s Era Club (later renamed the Ida B. Wells Club in her honor), and in 1913, in response to an Illinois law that allowed women to vote in certain elections (though not for all), she co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago with Belle Squire. The club focused on expanding voting rights for all women, encouraging civic engagement among Black women, and electing Black Chicagoans to city offices. Two years later, the Alpha Suffrage Club played a major role in electing Oscar DePriest as Chicago’s first Black alderman.

In 1913 the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA)—the famous suffrage group whose early leaders included Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and Carrie Chapman Catt—planned a suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The event drew suffragists from around the country to demand universal voting rights. A delegation from the Alpha Suffrage Club, including Ida B. Wells, also attended the march. The day of the march, the head of the Illinois NAWSA delegation told the Alpha Suffrage Club members that they wanted “to keep the delegation entirely white” and instructed all Black suffragists to walk at the end of the parade in a “colored delegation.” Wells waited with spectators until the parade was underway, and then stepped into the white Chicago delegation as they passed by.

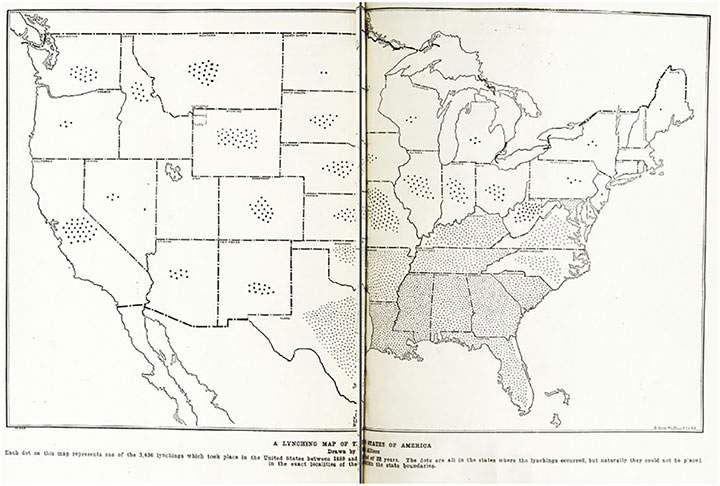

Above: NAACP map published in 1922, showing lynchings in the U.S. between 1889 and 1921.

Perhaps best-known among Wells’s work was the decades of investigative journalism work she devoted to researching and exposing lynchings. In 1909 she addressed the National Negro Conference, a forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which she co-founded with W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, and Moorfield Storey. In defining lynching, Wells said to the group, “First: lynching is color-line murder. Second: Crimes against women is the excuse, not the cause. Third: It is a national crime and requires a national remedy.” Between 1883 (the start of Wells’s data collecting) and 1950, more than 4,400 people had been lynched, with incidents in nearly every state of the Union. More than 4,000 of these were men, and 3,000 victims were Black (most lynchings of white and non-Black people of color occurred in the West and Southwest)—99 victims were women. Furthermore, as much of the data modern historians and sociologists use on lynching was uncovered by Wells herself, her statement was nothing short of revolutionary at the time. For decades, apologists for lynching and other extrajudicial murders held up rape and the “protection of women” as a justification. Yet according to a 2019 academic paper, a 1913 analysis of Wells’s data showed that while about a quarter of lynchings to date were supposedly in response to rape, only about two percent of Black men convicted of “major offenses” and imprisoned were sentenced for rape. Meanwhile, imprisoned whites at the time had much higher levels of rape convictions, suggesting that white offenders benefited from the legal system, while Black people accused of a crime were simply executed without arrest or trial. Furthermore, lynching was a key form of voter suppression and intimidation in the South: a 2017 study found that lynchings there reduced Black voter turnout by 2.5 points.

Judging by the news of late, we are still very far from finding a “national remedy” for this ongoing miscarriage of justice. In June of this year, four Black men were found hanging from trees in three different states—each death was ruled a suicide, despite the protests of the men’s families and national media attention. The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, first introduced in Congress in 1918, still hasn’t managed to be passed into law—nor have subsequent bills based on the original. The most recent version of the bill (the 2020 Emmett Till Antilynching Act which passed the House by a 410-4 vote) has been held up in the Senate by one man: Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky. He refused to honor his fellow senators’ wish to pass the bill by unanimous consent. As a result, lynching is still not a federal crime (or federal hate crime, as the Emmett Till Antilynching Act would classify it) in our country.

On top of that, extrajudicial murder by authorities continues unabated. So far in 2020, there have been just twelve days in which nobody in America was killed by a police officer. By the end of July, already 558 civilians had been fatally shot by police—111 of whom were Black. In 2019 the National Academy of Sciences noted that being killed by police was one of the leading causes of death for young Black men in America. One in 1,000 Black men and boys can expect to die at the hands of the police—that’s about 2.5 times more than white men and boys. (For comparison, the CDC states approximately 1 in 8,000 Americans die in car accidents each year.)

All of this is in addition to the “everyday” inequalities and injustice Black Americans face, whether they are “illegal” or not: persistent segregation in schools and neighborhoods; pay disparity based on both sex and race; lack of generational wealth; unfair housing practices; worse outcomes for Black mothers in childbirth; targeted voter suppression; the list goes on. And 2020 has heaped even more onto the pile, with COVID-19 disproportionately hospitalizing and killing Black patients. Wells was right to tie racial violence and inequality to universal suffrage: the problems are intersectional, and so must be the solutions.

Our 30th broadside, Truth or Consequences, is designed in red, white, and blue, symbolizing the rights of all Americans. Wells’s portrait sits in a ring of light while celestial symbols (stars, moons, wings) represent the light of truth. Her quote is presented in purple, the traditional color of the women’s suffrage movement — yet our broadside is only printed in red and blue. The text emerges where the two colors overlap to create purple: without this intersection of colors, the words are unreadable.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Truth or Consequences: No. 30 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 193

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed from hand-drawn lettering and illustrations on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

To help continue Ida B. Wells’s legacy, we are donating a portion of our proceeds to the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting, via an Action Grant from the Dead Feminists Fund. The Society is focused on increasing the ranks, retention, and profile of reporters and editors of color in the field of journalism and investigative reporting.

Purchase your copy in the shop

Colophon reads:

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett (1862 – 1931) was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her parents and infant brother died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1878, leaving her to care for five siblings. At 21 she moved to Memphis, commuting by train to teach at a rural school. After refusing to give up her purchased seat in a first class car, she was forced off the train. Wells filed and won a lawsuit in 1884, but the state Supreme Court reversed the decision. The experience launched her writing career, and she bought into a small newspaper, the Free Speech and Headlight. She began investigating the practice of lynching, calling it “a national crime [requiring] a national remedy.” By 1950 more than 4,400 people — most of them Black men, most in the South — were murdered, sometimes witnessed by crowds for entertainment. Wells published pamphlets filled with firsthand accounts and statistics, revealing a relentless regime of terror and oppression. In response, white mobs sent death threats and destroyed her printing press, forcing her to flee Memphis.

Moving north to Chicago, she also became a tireless worker for civil rights and women’s suffrage. In 1893 she founded the Women’s Era Club, a first-of-its-kind civic club for Black women in Chicago. She also co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club to focus on expanding voting rights for all women, and co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). At the 1913 Woman Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC, she and other Black suffragists refused to march in the rear, instead joining white marchers up front. Wells spent the rest of her life advocating for civil rights, equality, and universal suffrage for people of every race, class, and sex. She was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 2020, in recognition of her “outstanding and courageous” investigative journalism on lynching.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, in honor of women who stand at the intersection of feminism and racial justice, interrogating inequality. 193 copies were printed by hand at Springtide Press in Tacoma.