If you have any sort of link to the outside world (television, radio, internet access, newspaper, mailbox), chances are you’ve been unable to escape this year’s deluge of advertising, chatter and glossy-printed recycling fodder—all centered around this coming Tuesday. It’s enough to have even four-year-olds throwing up their hands in frustration. Jessica and I, however, have spent many hours sifting through election material—1972 election material, I mean. To remind us of what’s really important this year (and every year), we turned to the woman who help paved the way for our current President.

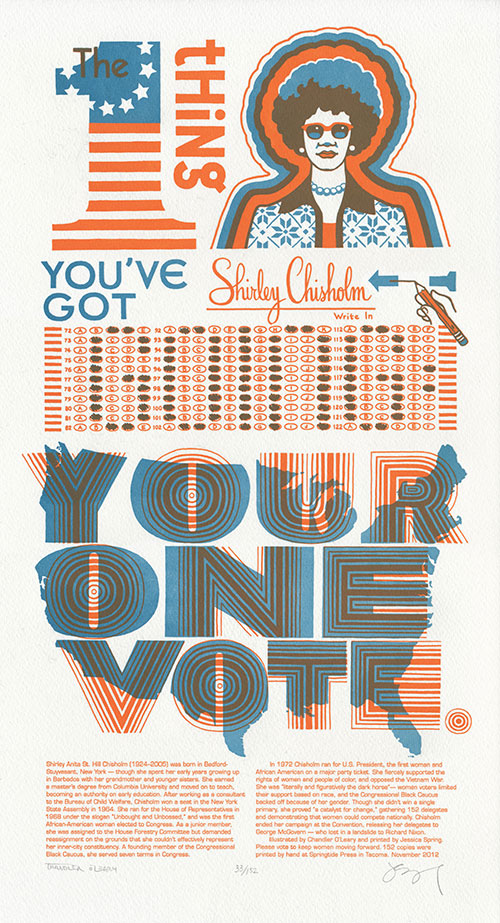

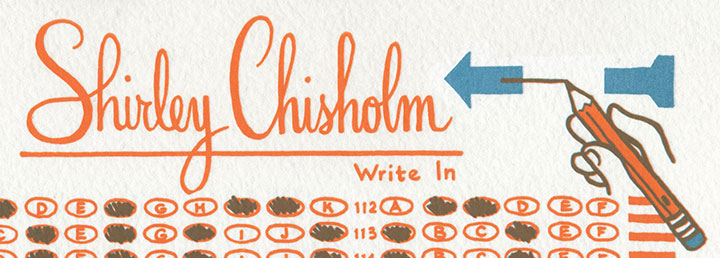

The one thing you’ve got going: your one vote. —Shirley Chisholm

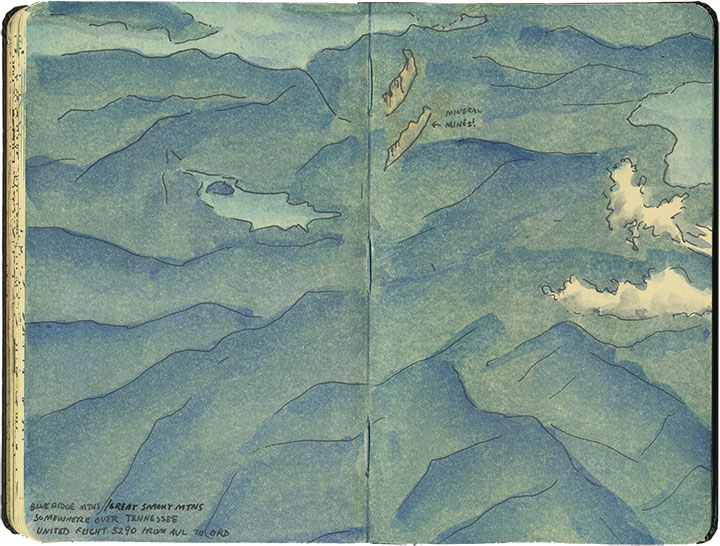

Shirley Chisholm was one of fifteen Presidential candidates in 1972. It was a volatile time: the Vietnam War was the center of public discord; movements for civil rights and gender equality were major issues around the western world; and the campaign came on the heels of the 1968 race—one of the bloodiest election years in American history.

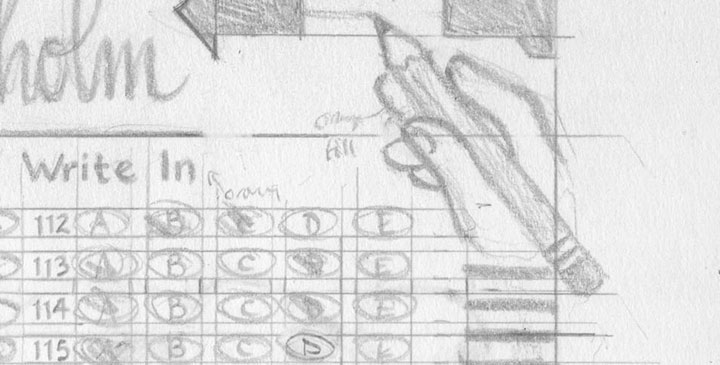

Shirley knew she was a long shot; she even referred to herself as “literally and figuratively the dark horse.” Yet she also knew that to run for President, all that was required was to be a natural-born U.S. citizen of at least 35 years of age. There was nothing in there about being male or Caucasian—and as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, she was at least as qualified as her fellow candidates. So she ran, because it was her right, and because she knew that if she played it smart and started winning delegates, she’d have some power to leverage.

Shirley sought to create a truly representative government. Rather than a cookie-cutter set of interchangeable politicians running the country, she envisioned an America where each region, economic sector and ethnic group elected one of its own to office. She wanted to see a woman heading the Department of Education & Welfare; a Native American in charge of the Department of the Interior. And as a freshman Congresswoman she was assigned to the House Forestry Committee but refused to serve—how would forest stewardship or agricultural bills represent New York’s inner-city 12th Congressional District?

She also saw her office as an opportunity to encourage women—especially women of color—to get involved in politics. Every member of her staff was a woman, half of them African-American. To say the least, her very presence made her fellow legislators nervous—and on top of everything else, she was probably the only woman of color in the whole country who made the exact same salary as her white male colleagues. (Heck, for people like Yvette Clarke or Barbara Lee, that’s probably still true for the most part. How depressing is that?)

On the national political stage, however, her race and gender were two strikes against her. She gathered support from the National Organization for Women, but when the time came for NOW to officially endorse a candidate, their squeamishness over the possibility of a Black nominee overcame their lip service. And the Black Congressional Caucus, of which Shirley was a founding member, threw her under a bus because they couldn’t bring themselves to support a female candidate. To me, that’s the most interesting thing—Shirley Chisholm always said she faced far more discrimination over her gender than the color of her skin.

Still, though she had to battle opposition and prejudice from all sides, she worked to bring people of all stripes together. When her opponent George Wallace (yes, that George Wallace—Mr. “Segregation Now, Segregation Tomorrow, Segregation Forever”) was wounded in an assassination attempt, Shirley visited him in the hospital. They were the ultimate Odd Couple: years later Wallace used his clout among Southern congressmen to help Shirley pass a bill giving domestic workers the right to a minimum wage.

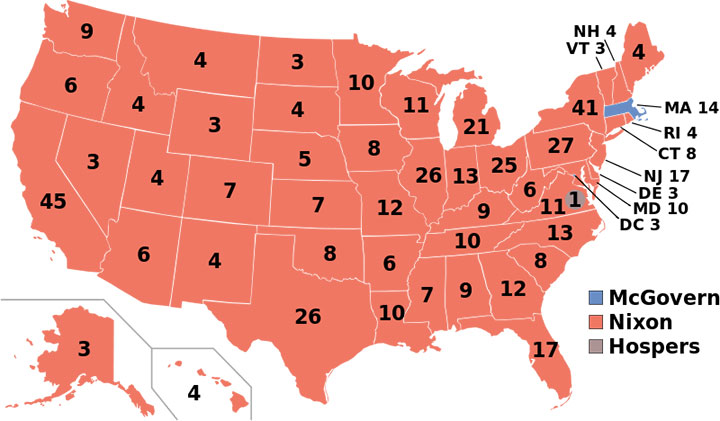

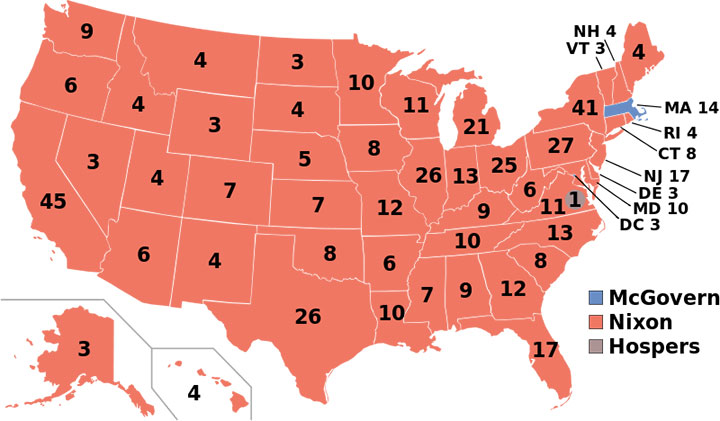

In the end, though she gathered 152 delegates, she knew she’d never snag the Democratic nomination. So she conceded to George McGovern—who went on to win just one state (Massachusetts) in the 1972 Presidential election. Take a look at the electoral college map for that year:

That’s a whole lotta red.

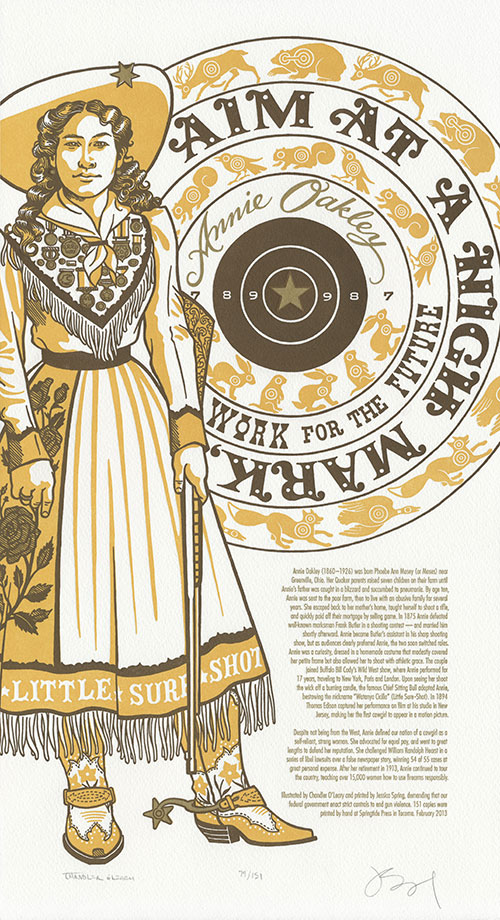

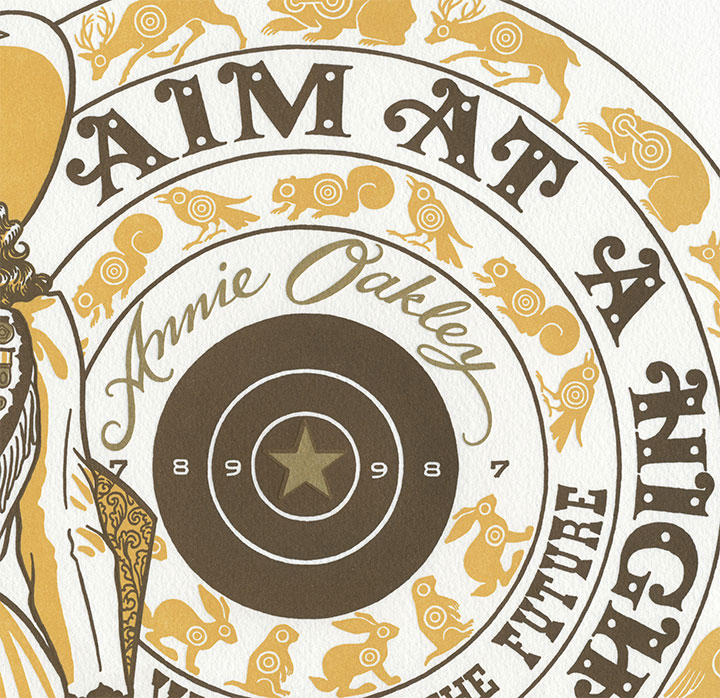

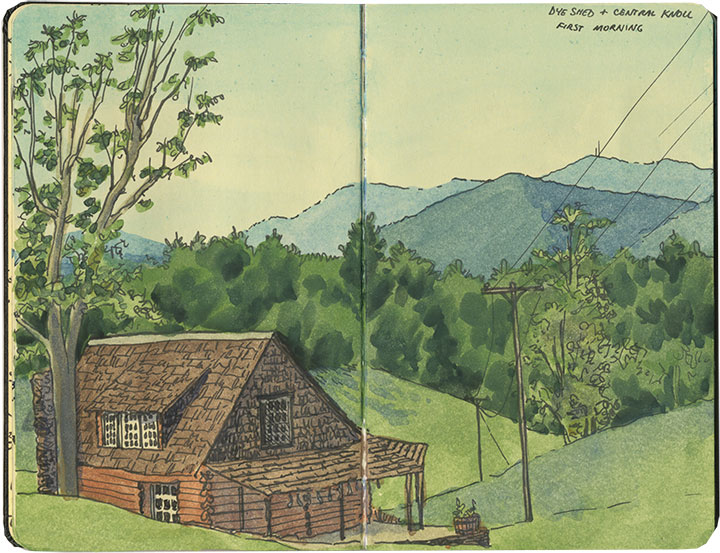

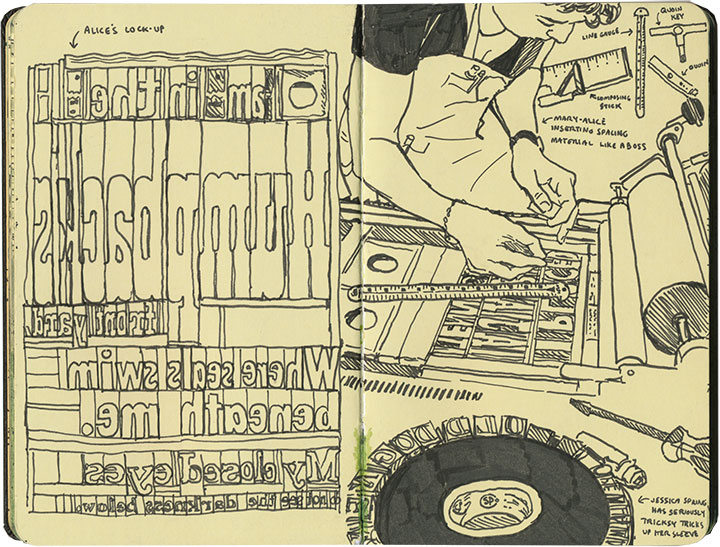

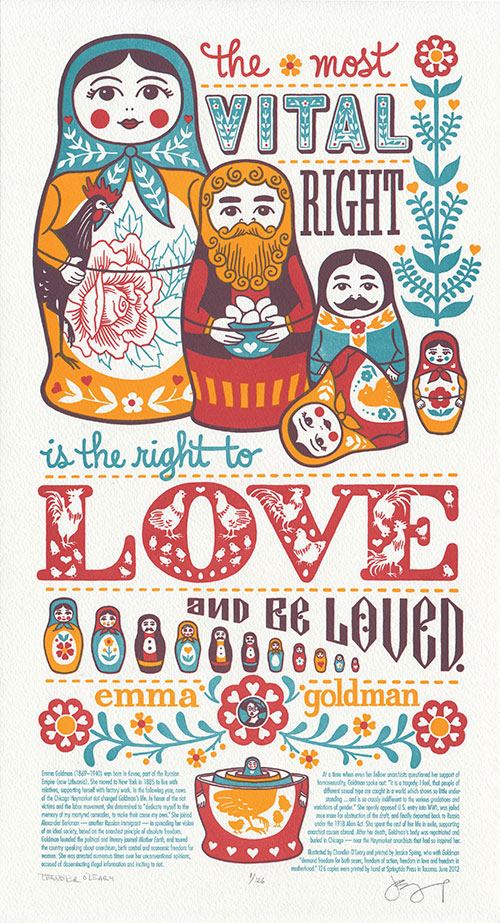

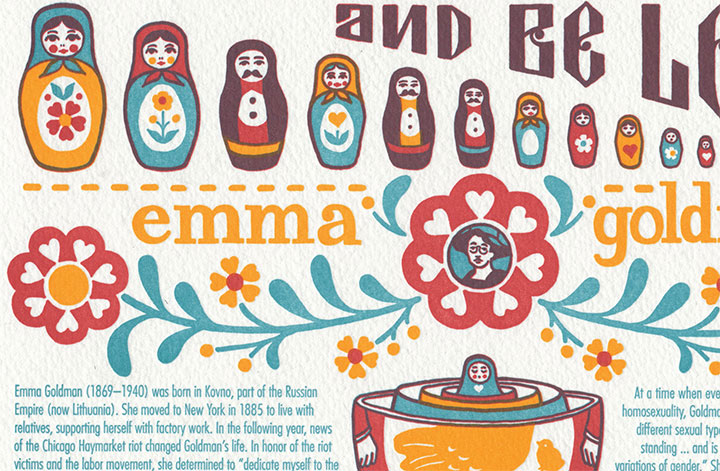

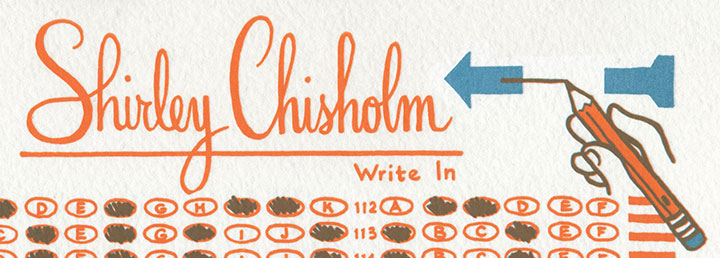

And since this election season marks the fourth anniversary of our series, that map was the starting point for Keep the Change, our new broadside. I redrew the map in blue, and from there we crafted a period homage to Shirley’s impeccable style and substance.

The 12th Congressional District was one of the areas hardest hit last week by Hurricane Sandy. While the immediate recovery efforts in the city are crucial, we also recognize the importance of serving a community long after the disaster relief efforts have ended. So to help continue Shirley’s long-term service to her home city, we’ll be donating a portion of our proceeds to Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration, the nation’s first non-profit community development corporation. Restoration partners with residents and businesses to improve the quality of life of Central Brooklyn by fostering economic self sufficiency, enhancing family stability, promoting the arts and culture and transforming the neighborhood into a safe, vibrant place to live and work.

In the meantime, let’s do what Shirley did best—cast our vote, and keep fighting the good fight.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

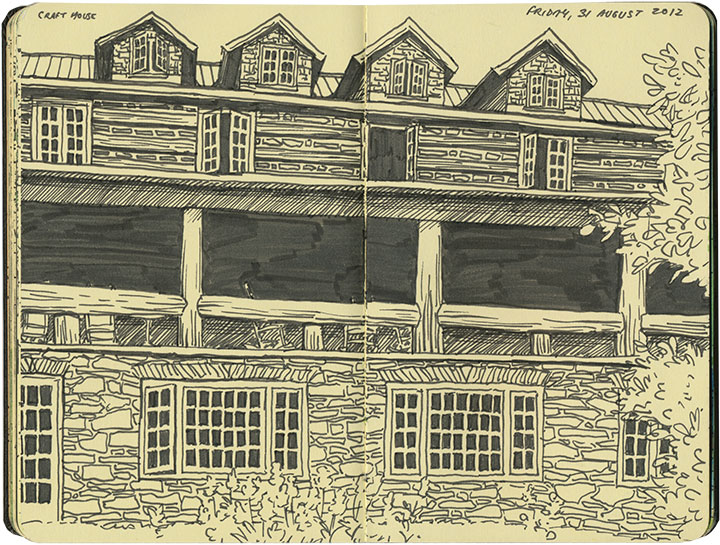

Keep the Change: No. 16 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 152

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

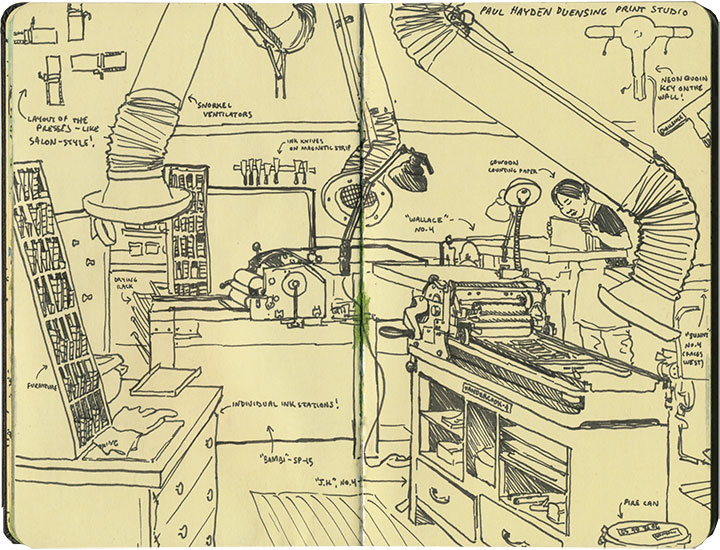

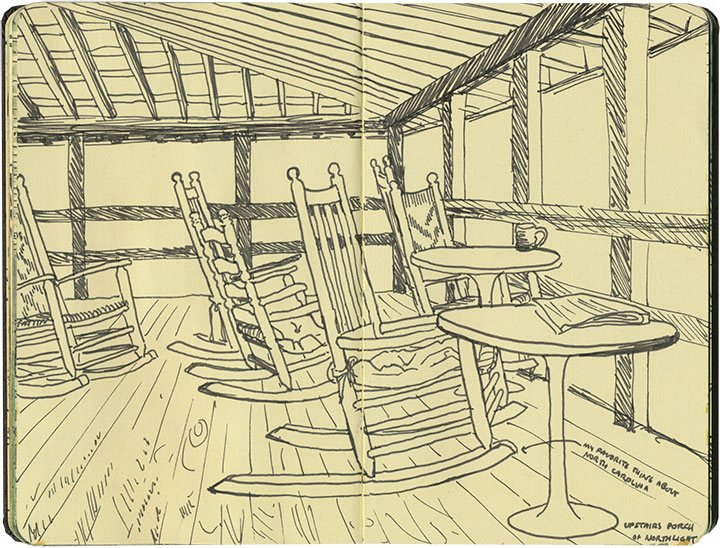

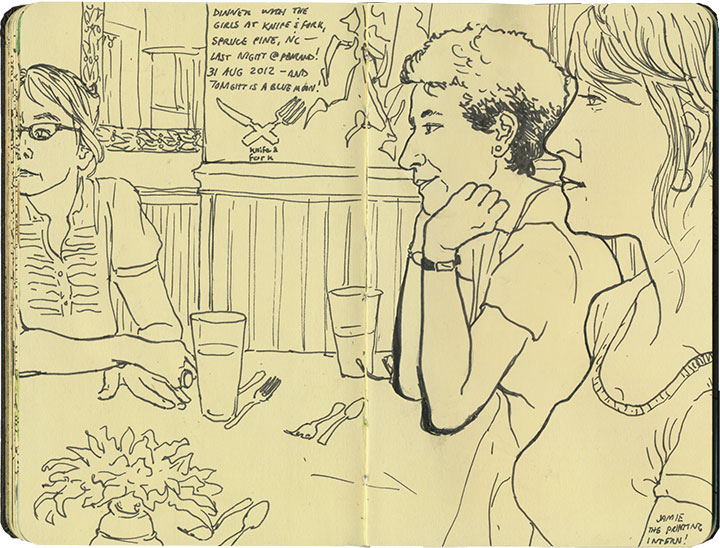

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm (1924–2005) was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York — though she spent her early years growing up in Barbados with her grandmother and younger sisters. She earned a master’s degree from Columbia University and moved on to teach, becoming an authority on early education. After working as a consultant to the Bureau of Child Welfare, Chisholm won a seat in the New York State Assembly in 1964. She ran for the House of Representatives in 1968 under the slogan “Unbought and Unbossed,” and was the first African-American woman elected to Congress. As a junior member, she was assigned to the House Forestry Committee but demanded reassignment on the grounds that she couldn’t effectively represent her inner-city constituency. A founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, she served seven terms in Congress.

In 1972 Chisholm ran for U.S. President, the first woman and African American on a major party ticket. She fiercely supported the rights of women and people of color, and opposed the Vietnam War. She was “literally and figuratively the dark horse”— women voters limited their support based on race, and the Congressional Black Caucus backed off because of her gender. Though she didn’t win a single primary, she proved “a catalyst for change,” gathering 152 delegates and demonstrating that women could compete nationally. Chisholm ended her campaign at the Convention, releasing her delegates to George McGovern — who lost in a landslide to Richard Nixon.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring. Please vote to keep women moving forward.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the shop!