Midterm elections are looming, and we have a lot of work ahead of us. We knew right away that with this being an election year, we wanted to feature voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer for our next Dead Feminists broadside. But before long we realized that Hamer could carry us down the rabbit hole, with seemingly endless social issues to investigate through the lens of her life and work. Which should be the focus for our broadside? Where would we even start? We could have chosen any number of things, just based on Hamer’s story. Her Congressional bid evoked the contemporary groundswell of women newly running for office. Her forced sterilization in 1961 brought up reproductive rights and the Pro-Choice movement’s shadow history of racist eugenics. Her survival of a beating in a county jail underscored this country’s persistent police brutality against Black citizens. Her work with community agriculture reminded us of America’s continued lack of food security and equal access to nutrition for the working poor. And taken together, all of these myriad issues and problems are distilled and rarefied by Hamer’s simple truism:

Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.

It was that simplicity that swayed us in the end: Hamer started with focusing on the vote, and so did we. As the midterms approach, it is increasingly obvious to us that turning out the vote is the only way to turn the rising tide of state-sanctioned inequality and violence. It is more important than ever to help continue Hamer’s work, to combat racism and make sure that all Americans have the same access to their constitutionally-protected rights of suffrage. That task is as difficult as it’s been in decades, thanks to the Supreme Court overturning key portions of the Voting Rights Act in 2013. And Black voters—those voters who most reliably stand for progressive causes and candidates, and who are already disproportionally targeted for disenfranchisement—are feeling the effects of that ruling. If progressives want their help in November, we need to help them first.

Fannie Lou Townsend was one of 20 children born to a family of sharecroppers in Mississippi; by the time she was a teenager, she was picking up to 300 pounds of Mississippi Delta cotton per day, despite a permanent leg injury from having polio as a child. Though she was only able to attend school through age 12, she loved learning and was an avid reader—years of Bible study forged for her a personal connection between scriptural stories of liberation and the modern Civil Rights movement. In 1945 she married Perry “Pap” Hamer, a fellow sharecropper, and the couple later adopted two daughters. In 1962 she attended her first mass meeting—it was there that she learned for the first time, at the age of 44, that Black people had the right to vote. A few days later she and sixteen others boarded a bus to Indianola, MS to register as voters (her attempt was unsuccessful, thanks to literacy tests and poll taxes)—and the following day, she was fired from her plantation job. Pap was fired shortly afterward.

Hamer continued to try to register to vote, and started helping others attempt to overcome the racist literacy tests, poll taxes and transportation challenges that stood in the way. As her interest in direct action for civil rights increased, so did the attempts to silence her. Days after she lost her plantation job, she survived a drive-by shooting attempt by white supremacists. In 1963, while on a bus trip with fellow activisits from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Hamer and several others were arrested after being refused service at a cafe in Winona, MS. After being taken to the county jail, a state trooper took Hamer into a cell and ordered two inmates to beat her with blackjacks while the police held her down and groped her. The state trooper then joined in on the near-fatal beating, leaving Hamer with permanent damage to her legs, eyes and kidneys. She kept up her activism anyway: “I guess if I’d had any sense, I’d have been a little scared — but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

After the police beating, Hamer traveled widely on a public speaking tour—sharing her story, singing gospel hymns, gaining followers and raising money for civil rights groups. In 1964, after co-founding the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (which helped expand Black voter registration and challenged the state’s all-white hold on the party), she ran for Congress. Her bid against a white incumbent was unsuccessful, but in an interview with The Nation she said, “I’m showing the people that a Negro can run for office.”

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party continued to grow, agitating for change to the system of seating only white Mississippi Democrats at the Democratic National Convention. Hamer and her fellow MFDP members traveled to the 1964 Convention to stand as the state’s official delegates, with Hamer was chosen as the party’s speaker—prompting the white delegates to walk out in protest. President Lyndon Johnson—who generally supported the Civil Rights movement and signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965—feared he’d lose his bid for reelection without the support of white Southern Democrats. To appease them and bolster his own campaign, he preempted the broadcast of Hamer’s convention speech by holding a nationally-televised press conference at the same time. Finally, in 1968 the national Democratic Party changed its rules to require equal representation from its states’ delegates, and the MFDP was seated at that year’s National Convention alongside the white Southern Democrats. In 1972, the same year that Shirley Chisholm ran for President, Hamer was elected as a national party delegate.

Hamer’s voice continued to inspire her national following, even as she narrowed her focus back to her native Sunflower County, Mississippi. In the late 1960s she lent her time, money and energy to a number of grassroots efforts there, including a communal farm and livestock share program to increase food security and nutrition equality among the sharecroppers and rural Black residents. She argued that self-sufficiency was the best path to full citizenship for Black Mississippians, and promoted land ownership and crop control as essential civil rights. She enlisted the help of a Wisconsin nonprofit called Measure for Measure, and secured a large celebrity donation from Harry Belafonte, to found the Freedom Farm Corporation and begin buying up Mississippi Delta farmland. By 1971, despite threats by white supremacists, Hamer had acquired over 600 acres for use in communal agriculture: “If we have that land, can’t anybody starve us out.”

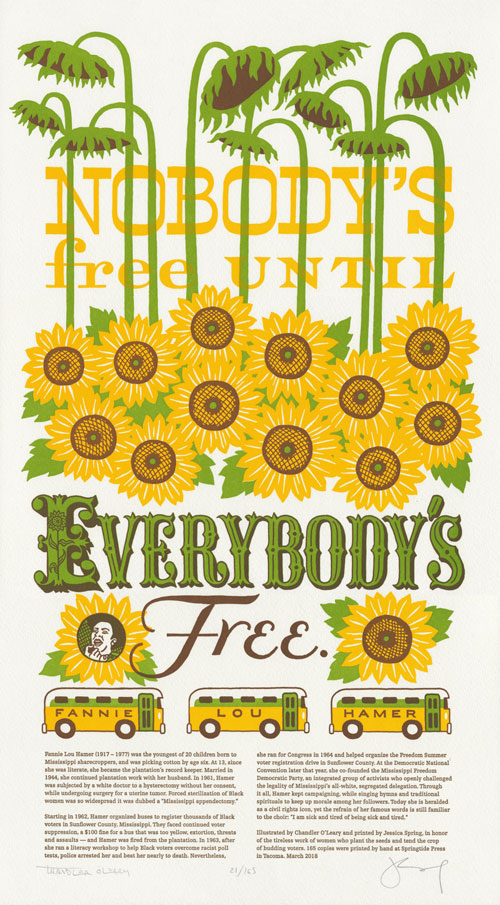

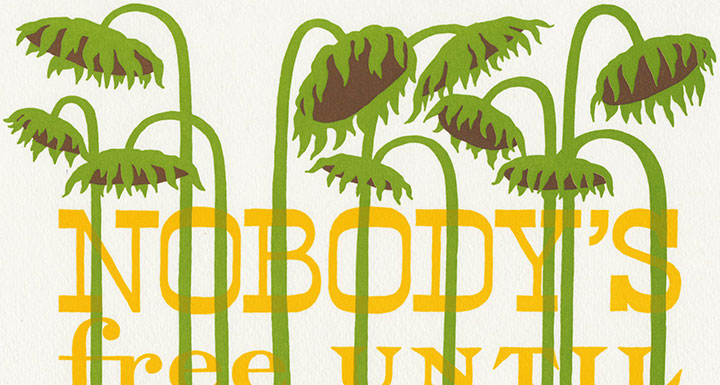

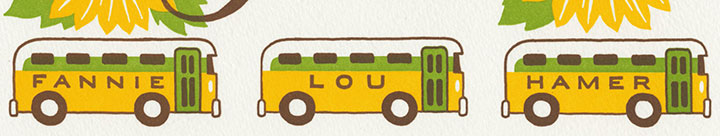

Our 27th broadside, Seeding the Vote, honors Sunflower County, where Hamer planted so many seeds for freedom, suffrage and full citizenship for all. The first half of the quote sits “behind bars,” obscured by the stalks of wilted sunflowers, while the second half is festooned with vibrant yellow blossoms. Hamer’s portrait hovers above a trio of her iconic yellow voter registration buses—which are also designed to be reminiscent of other Civil Rights Movement buses in the American South, including Rosa Parks’ famous bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

To help combat the same racist disenfranchisement that Fannie devoted her life to fighting, we are donating, via a grant from the Dead Feminists Fund, a portion of our proceeds to Spread the Vote, a nonprofit that obtains government-issued photo IDs to help eligible voters meet the requirements of voter ID laws. Currently 34 states have some form of voter ID law as a requirement for enfranchisement; many of the strictest laws exist in states with a large percentage of Black or other minority voters. With their IDs obtained with the help of Spread the Vote, these same people can also secure housing, jobs and other essentials more easily—helping them participate more fully in society and exercise their rights as Americans.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the shop!

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Seeding the Vote: No. 27 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 165

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917 – 1977) was the youngest of 20 children born to Mississippi sharecroppers, and was picking cotton by age six. At 13, since she was literate, she became the plantation’s record keeper. Married in 1944, she continued plantation work with her husband. In 1961, Hamer was subjected by a white doctor to a hysterectomy without her consent, while undergoing surgery for a uterine tumor. Forced sterilization of Black women was so widespread it was dubbed a “Mississippi appendectomy.”

Starting in 1962, Hamer organized buses to register thousands of Black voters in Sunflower County, Mississippi. They faced continued voter suppression, a $100 fine for a bus that was too yellow, extortion, threats and assaults — and Hamer was fired from the plantation. In 1963, after she ran a literacy workshop to help Black voters overcome racist poll tests, police arrested her and beat her nearly to death. Nevertheless, she ran for Congress in 1964 and helped organize the Freedom Summer voter registration drive in Sunflower County. At the Democratic National Convention later that year, she co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, an integrated group of activists who openly challenged the legality of Mississippi’s all-white, segregated delegation. Through it all, Hamer kept campaigning, while signing hyms and traditional spirituals to keep up morale among her followers. Today she is heralded as a civil rights icon, yet the refrain of her famous words is still familiar to the choir: “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, in honor of the tireless work of women who plant the seeds and tend the crop of budding voters.