Holy cannoli, everyone! I’ve only just now come up for air—I’ve been buried under invoices, subscription forms, kraft mailers, and email print-outs, and Thea’s face is repeated all around me as reserved copies are spread all over the studio. Since I posted her here on Tuesday night the orders have just poured in, and over three-quarters of the edition is spoken for already. And Prop Cake is disappearing fast, too; we’re down to our last handful. Wow—just…wow. Thank you all so, so much.

Since Jessica and I talked about our process at the Tacoma Art Museum the other day, we thought it made sense to share that process with you, as well. But since there’s rather a lot to say on the subject, I’ve decided to break it into two posts.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Before I get into the technical details behind our series, I should probably share a little background information on letterpress and the art of the broadside. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the process, letterpress printing refers to a type of relief printing, where pressure is applied to a piece of paper placed over a raised form that is covered with a thin layer of ink. This pressure transfers the inked image onto the paper, and can be repeated to create a batch, or edition, of prints. The form can be a carved block of wood or linoleum; a raised plate made of magnesium, photopolymer (plastic) or other materials; or as the term letterpress implies, movable type made from metal or wood.

The innovation of printing words from individual letter blocks that can be rearranged and reused was actually invented by the ancient Chinese (seriously, what wasn’t originally invented in China? We owe those folks a whole heap), but the process that evolved into modern letterpress was most famously perfected over 500 years ago by Johann Gutenberg, of Gutenberg Bible fame. By the first half of the twentieth century, when more modern commercial printing came along, it was still common for printers to perfect their layouts using movable type and relief-cut images on a proof press (such as Jessica’s Vandercook below). They’d then use the resulting print to make more sophisticated plates for their more efficient and advanced commercial presses.

As commercial printing became more streamlined, the cylinder and platen proof presses (see photo of Jessica printing above) fell out of vogue, and eventually were no longer manufactured. Artists quickly saw their potential, however, and have adopted letterpress printing as an art form—using, refurbishing and maintaining this antique equipment to create original works of art.

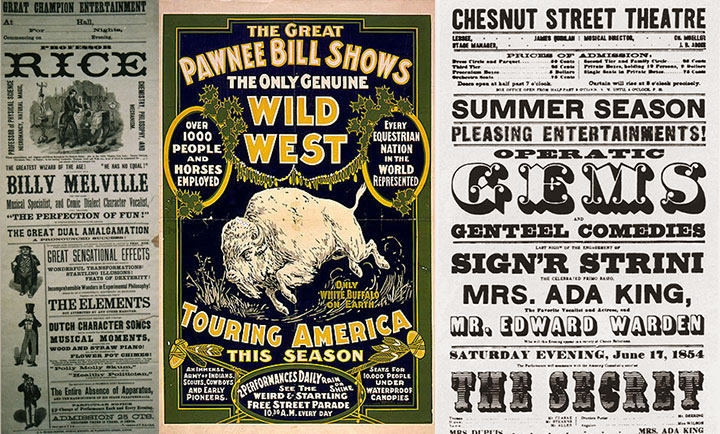

Hand-in-hand with letterpress printing, the art of the broadside has also survived and evolved into a modern format. The term broadside means any single sheet used to convey information, often of a political kind—the great-grandpappy of the modern poster. While today the words broadside and poster are sometimes used interchangeably, the broadside has remained a favorite of the letterpress community because of its emphasis on typography and content (hey, we need an excuse to use all that gorgeous metal type!).

Jessica and I had this history in mind when we began the Dead Feminists series. As I said before, we never dreamed of starting down the path we’re on now; we just wanted to make a political and artistic contribution to the election. And to pay homage to the history of the broadside and the era in which each of our feminists lived, I designed each piece with historic broadsides and posters in mind. And to keep the series consistent, Jessica and I came up with a few rules of engagement:

1. Each poster has to feature a quote by a feminist. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a woman, but there are already plenty of posters highlighting the words of dudes, so we figured that one was covered already.

2. Said feminist must be deceased. (Hence the name.) You’d be surprised how many challenges that’s created for us.

3. Each quote is tied into a current sociopolitical issue or event. This is usually Jessica’s job, as she’s got a particular knack for finding relevant quotes.

4. The whole piece (except the colophon at the bottom, of course) is hand-drawn.

5. We try to stay away from well-worn tropes like “women can do anything men can do!” in favor of broader topics and concepts.

Who knows how long people will be interested in these things, or how many broadsides there’ll be in the series—all we can say is that we’re grateful for the response people have had, and we’re having way too much fun to quit now. The fun of art-making and the joy of the public response aside, the best part of creating this series has been exploring the lives and work of so many inspirational people. “Feminism” has become somewhat of a dirty word these days—mostly because of misconceptions. To us it’s a positive thing, and creating this series is our way of celebrating those who championed far more than just gender equality. Besides, we’d like to make our own contribution to our social history—and using the “power of the press” in the literal sense is the best way we know how.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Coming in part two: the nitty gritty details behind our process.